Editor’s Note: The student newspaper of Karns High School is a public forum, with its student editorial board making all decisions concerning its contents. Opinions in the paper are not necessarily those of the staff, nor should any opinion expressed in a public forum be construed as the opinion or policy of the administration, unless so attributed.

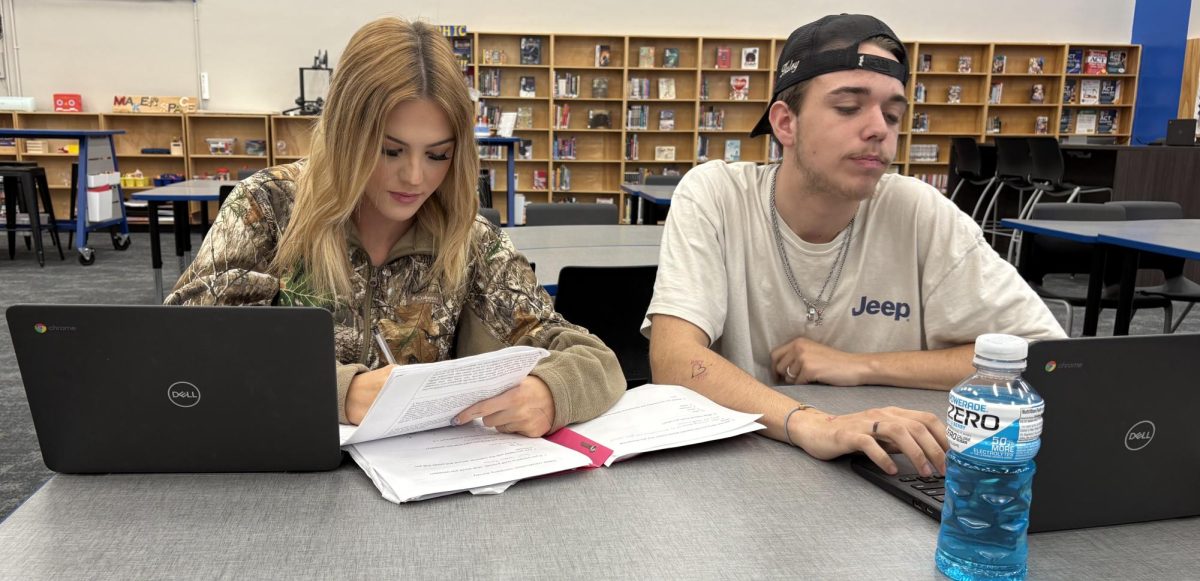

Knowledge is power, but in Knox County Schools, that power is being undermined this year, as over 100 books have been quietly removed from library shelves. Critical, award-winning literature has continued to be taken out of our libraries without student input. The removed titles span many genres — from children’s books like “Draw Me A Star” by Eric Carle to American classics such as “Slaughterhouse Five” by Kurt Vonnegut. Here, at KHS, students are asking: What do these books have in common? Why are they no longer available to us at Karns High School?

Originally described as a “book challenge,” the actions are now only correctly described as a book ban, due to the formal actions that have been taken to eliminate these books from school libraries. The Knox County School Board says this removal is an effort to eliminate “explicit” material from everyday student access, citing Tennessee’s newly expanded Age-Appropriate Materials Act . This law, revised in December 2024, has resulted in the removal of more than 100 titles from school libraries across the district, including here at Karns High School.

While the “Age Appropriate Materials” cited purpose is to shield students from “excessive violence, nudity, or sexually explicit content,” its application tells another story. Some people claim the books being removed are disproportionately targeted or based on specific topics. Many of the titles that have been removed share common threads: they often feature LGBTQ+ characters, discuss race and systemic inequality, or are written by authors of color. For example, “The Bluest Eye” by Toni Morrison, a Nobel Prize winning novel that discusses racism and trauma, has been pulled from the shelves. “All Boys Aren’t Blue” by George. M Johnson, a coming of age memoir about growing up black and queer is also gone. “Out of Darkness” by Ashley Hope Perez, a critically acclaimed historical novel exploring racism and segregation has been similarly removed, along with dozens of other titles that tackle complex, real world issues.

For students of Karns High School, the effects of this are already felt. Books that once challenged our thinking and expanded our understanding of the world are no longer accessible within our school walls. In their place? A narrowed list of titles deemed “safe” enough for middle schoolers — now serving as the limit for high school seniors as well. This is largely due to the language in Tennessee Code Section: 49-6-3803 (b)(2), which states that that any material that is found “patently offensive” or that “appeals to the prurient interest” is “not appropriate for the the age or the maturity level of a student in any of the grades kindergarten through twelve (K-12)” and must not be kept in a school’s library. However, applying the same rules to both kindergarteners and 12th graders gets rid of important developmental differences, and denies older students the opportunity to engage with complex, age-appropriate literature.

In theory, part of the school district’s mission is to “provide excellent and accessible learning opportunities,” but in reality, these removals risk doing the opposite.

As the National Coalition Against Censorship (NCAC) stated in a June 2025 letter to the Knox County School Board, “Removing books like these puts your students at an educational disadvantage and is contrary to the district’s mission to empower students to become life-long learners who are able to meet the challenges of a changing society.”

Despite the NCAC’s outreach, the Knox County School Board has failed to respond.

Inside the Library: A Conversation With Mrs. Newman

Mrs. Newman, our head librarian at Karns, went into detail about how this law has affected her job and the Library here at Karns High School.

“When the law came through, we had to dig deeper,” Newman said, “We had to have extra training on what to look for, It’s such a grey area.”

This process has not only limited access for students but has also placed an extra strain on staff.

“It was gut wrenching,” Newman said, “It felt like we couldn’t be trusted with our knowledge and education.”

She explained how school librarians were re-trained to flag material that could be interpreted as inappropriate, even if the content was age appropriate for highschoolers. That’s led to broad removals across grades, regardless of context.

“Even if it’s not middle school appropriate we still have to get rid of it here [in highschools],” Newman said.

Newman also mentions how these losses are not going completely unnoticed.

“Overall, students are confused, my big readers come in looking for certain books, and I have to explain why they’re gone,” Newman said.

When school districts remove books from students, they are also removing resources for students to learn, research, and become educated members of their communities. This removal poses a contradiction to the entire purpose of public schools; to provide accessible learning opportunities for everyone.

Inside the School: Classroom Libraries

At Karns High School, the library isn’t the only place where books are disappearing, it’s happening in classrooms too. According to Knox County Schools:

“In August of 2022, the Tennessee Department of Education determined that the Age Appropriate Materials Act (AAMA) applies to the classroom libraries as well as school libraries. So beginning in the 2022-2023 school year, the contents of all classroom libraries in Tennessee must be posted transparently on school websites.”

The policy was expanded upon in July 2024, when new amendments to the AAMA further tightened the restrictions across books, and furthermore, what could be kept in classroom libraries. The school district explains:

“Books KCS has identified as affected by this law must also be removed from classroom libraries.”

In practice, this means that teachers are now responsible for documenting and uploading every single book in their personal shelves for review, while also keeping up with lesson plans, grading, and parent communication. Many teachers — facing the same scrutiny and policies as librarians — have packed up their classroom libraries altogether rather than go through the time consuming process of scanning and approving every title.

“I know that a lot of teachers at this point said, I’m just going to go ahead and box up these books, we’ll put them away, so there are no issues,” explained April Shoults, an English teacher at Karns, “In the grand scheme of things teachers don’t want issues, they just want to come in and teach their students, and help them progress to the next level, and become good citizens within their community.”

She also pointed out how the law could potentially impact students with low income backgrounds or limited resources.

“What if students don’t have access, or have parents with a car readily available to go check out those books, if they don’t have the money to buy those books?” Mrs. Shoults said, “That causes issues with them being able to access those books and information that they are interested in reading.”

For Mrs.Shoults, another concern is what happens when books are pulled without student input and thorough review.

“When we start removing books indiscriminately, and without having people vetted who have entirely read through the books… then we just start picking and choosing and it can limit what kids read, and therefore decrease their passion for reading.”

What’s Being Lost?

It isn’t just about books missing from shelves — it’s about what those books represent. Literature isn’t just used academically, as Newman explains.

“We’re taught in library school that books are mirrors and windows, you should see yourself, or someone else — so you can learn empathy,” Newman said.

Literature also develops critical thinking, curiosity, and emotional intelligence. Many of the books being removed deal with complex issues — race, identity, trauma. These are not necessarily dangerous ideas; they are a part of the world we live in. Taking away these books from students at Karns High School means denying us opportunities to process, understand, and engage with the world we live in. It also sends a message — these topics are being deemed too controversial, too difficult, or too dangerous to learn about in school.

“Reading develops critical thinking,” Newman adds, “When you take away books, you risk taking away those skills.”

What’s changed, and who’s influencing these decisions?

What’s most frustrating about the recent wave of book removals at Karns High School and across Knox County Schools is this: a system to handle concerns about library materials already existed — and it worked. Under the district’s previous policy, if a parent, student, or staff member believed a book was inappropriate for school use, they could file a request for reconsideration. This would trigger a structured and collaborative review process. A school-level committee, typically composed of teachers, administrators, librarians, and sometimes even parents, would read the book in full, evaluate it using educational standards, and consider its library merit. If needed the decision could be appealed to the district for further review.

This system was built on both student and parent input, along with professional judgement, but this year, that system has largely been bypassed when it comes to removing books.

What was once a thoughtful inclusive process, has been placed by blanket removals made by councils downtown — often driven by outside pressure and vague legal definitions or what’s interpreted as “inappropriate.”

So who is influencing these removals? Popular advocacy groups like Moms For Liberty have organized national campaigns pressuring school boards across the country, including Tennessee to pursue mass removal of books they claim don’t align with the views of family values or age-appropriate content. Other supporters of Tennnessee’s Age Appropriate Materials Act argue that it protects children from explicit or harmful content, and gives parents more oversight.

While these concerns may be well intentioned, the reality in our schools and classrooms feels more like restriction and censorship than protection — especially when books are removed without actual student input.

A Personal Note From A Student

When I began writing this article, I intended to present a neutral account of the changes in our school system and in our libraries. But as a 17 year-old, and a senior preparing to enter the adult world, I can’t ignore the reality. My access to a range of literature that once challenged and inspired me has been replaced by silence. My options are now being limited, our options as a student body at Karns High School are limited.

The law implies that all books available to me must also be appropriate for an elementary and middle school student, but I’m not in elementary school. Like so many other seniors, I’m nearly an adult. I’m curious about the world I’m about to enter, and want to understand the issues that shape it.

Books teach us empathy. They help us question reason and reflect. If we only offer students literature that is comfortable, simple, and uncontroversial, then we deny them the resources needed to become thoughtful citizens.

“Books with heavy topics are not going to harm children,” author George M. Johnson once said, “Having books gives them tools… the language, the resources. So that when they are having to deal with a heavy topic, they have a roadmap.”